Garraway’s Coffee House

In 1651, a young member of an English family active in the Levant trade left Izmir (or Smyrna as it was then known) to travel with his personal assistant to London. This Daniel Edwards married Mary Hodges, the daughter of another Levant merchant and the Hodges/Edwards household became a great attraction for other merchants who had sampled coffee on their travels to the Levant. The house became so busy with friends coming round for a cup – or dish as they usually referred to it then – of coffee, that Edwards and Hodges decided to open a coffee house in the style they had experienced in Turkey; that is, a place to have a drink and a chat with like-minded souls, but also a place to hear or read about the latest news and to meet business associates. In 1652 (or 1657, depending on which source you believe), they set up Edward’s assistant, Pasqua Rosée, as the manager of the first London coffee house in St. Michael’s Alley, close to the Royal Exchange which was bustling with traders, lawyers, booksellers and merchants, many of whom had been to Turkey and were familiar with the coffee houses there and were hence seen as prospective customers.

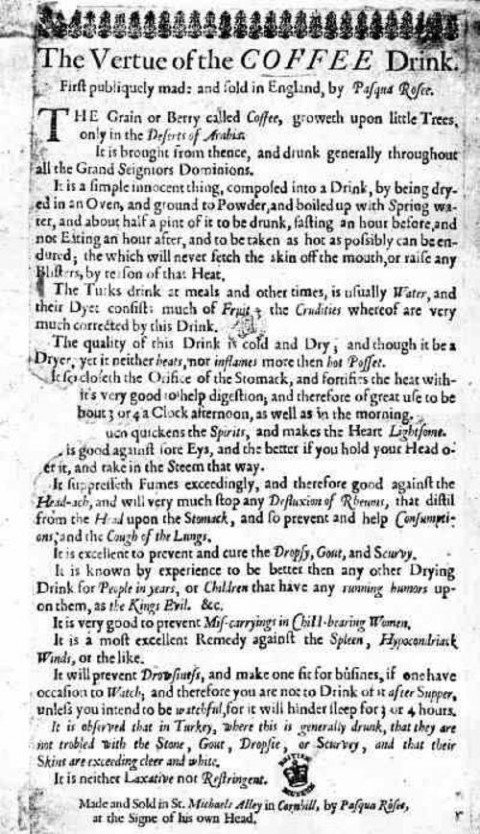

Pasqua’s success led from one thing to another and within a very short space of time, London was teeming with coffee houses where anyone, regardless of social standing, could come in for a drink, a chat and to read the newspapers. A handbill was printed to list all the positive effects of drinking coffee, such as to “prevent and cure the dropsy, gout or scurvy”, and it was also considered an “excellent remedy against spleen, hypocondriack winds, or the like”.

First advertisement for coffee -1652: Handbill used by Pasqua Rosée, who opened the first coffee house in London – From the original in the British Museum.

Coffee houses were such a great success, not least because the Puritan government at the time frowned upon taverns and ale houses as licentious and wicked places where public order was disturbed and people were led into ruin and destruction. Ironically, the coffee houses themselves were soon seen as hothouses of dissent where anyone could voice an opinion and spread rumours.

In 1672, Charles II issued A Proclamation to restrain the spreading of false news, and licentious talking of matters of State and Government. Coffee houses were particularly mentioned as the places where such anti-government talk was rife and the public was urged to report such discussions. Not that the proclamation had any effect, and in 1674 a similar proclamation had to be published and at the end of 1675 an even more severe one: A proclamation for the suppression of coffee-houses. The coffee house owners obviously feared for their livelihood and used their influence with their patrons, some of whom had great influence at Court, to have the proclamation rescinded.

The coffee men found a willing ally in Andrew Marvell whose ‘Dialogue between Two Horses’ (1676) ridiculed Charles II and asserted that:

Though tyrants make laws, which they strictly proclaim,

To conceal their own faults and to cover their shame,

Yet the beasts in the field, and the stones in the wall,

Will publish their faults and prophesy their fall;

When they take from the people the freedom of words,

They teach them the sooner to fall on their swords.

Let the city drink coffee and quietly groan, –

They who conquered the father won’t be slaves to the son.

For wine and strong drink make tumults increase,

Chocolate, tea, and coffee, are liquors of peace;

No quarrels, or oaths are among those who drink’em

‘Tis Bacchus and the brewer swear, damn’em! And sink’em!

Then Charles thy edict against coffee recall,

There’s ten times more treason in brandy and ale.

In the end, a very watery compromise was reached where stricter regulations and licences were enforced upon the coffee houses and where self-regulation was supposed to curb the freedom of speech and the production of dissenting libels.

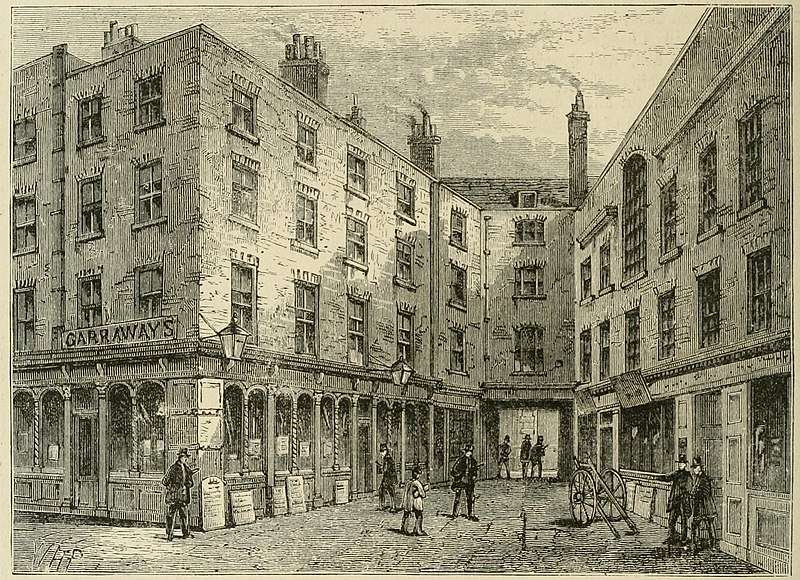

The remark about the people of quality comes from “A Journey through England”, in which the author mentions Garraway’s as one of three celebrated coffee houses in Exchange Alley where “People of Quality who have Business in the City, and the most considerable and wealthy Citizens frequent”. But wealthy citizens were not the only clients of the coffee house. Charles Dickens wonders where the unsuccessful ones that wait all week for the business opportunity that never comes go. He thinks that perhaps Garraway takes pity on them and lets them stay the Sunday in the old monastery crypt under the premises.

A frequent visitor of Garraway’s was Robert Hooke (1635-1703), the often cantankerous curator of experiments of the Royal Society and one of the Surveyors to the City of London after the Great Fire. He did not just frequent Garraway’s, but also, among other establishments, Jonathan’s in Change Alley and Child’s in St. Paul’s Churchyard. At the end of December 1675 he is at Garraway’s almost every day and remarks on the 30th on the Proclamation to shut down the coffee houses in his usual abbreviated style “To Garaways Green Room, Hill, &c. proclamation against Coffee house” and later that day “Discourse about proclamation”.

The building was destroyed by fire in 1748, having been open for 216 years.